The Happiest and Saddest Day

A story from Gary, an Outside The Walls Centering Prayer group member

About halfway through my twenty-year prison sentence, I told my mom, “The day I leave this place will be the happiest and the saddest day of my life.”

The happiest—because I would finally regain my liberty after decades behind bars. The saddest—because by then, prison had also given me brothers. Men I lived with, worked with, prayed with. Men whose presence softened the daily dehumanization of incarceration. Without those relationships, many of us would not have survived.

That paradox has never left me.

Discovering God in Silence

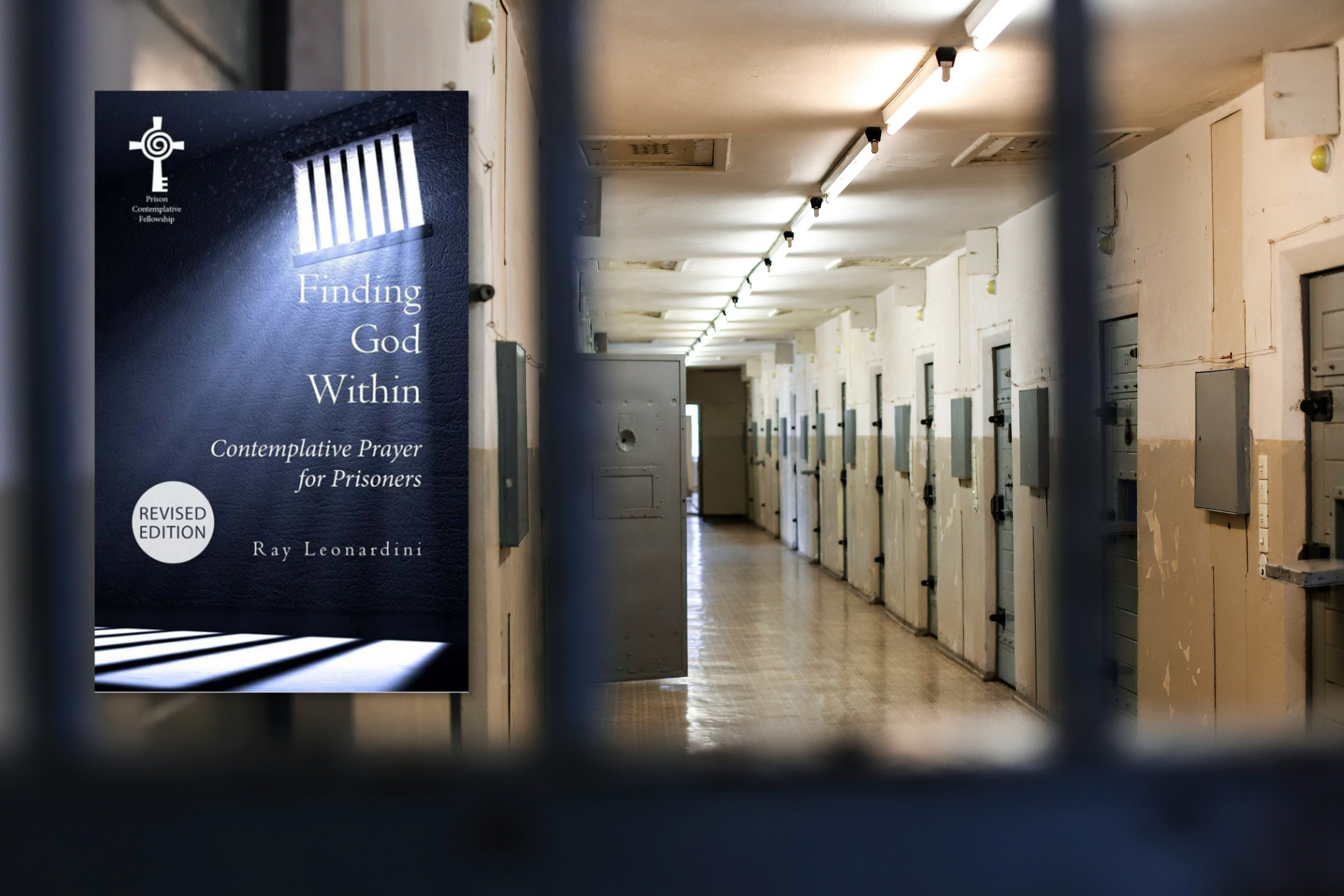

Around 2012, I found a newsletter from the Human Kindness Foundation by the microwave. Inside was an offer for a free book: Finding God Within by Chaplain Ray Leonardini. Since I loved books—and free things—I wrote to request a copy. I was also searching. I had already encountered the Spirit of God once before, in the crushing isolation of a suicide-watch cell, but I longed for something deeper, something steadier than the routines of organized religion.

The book told the stories of men who had experienced God, not through sermons or hymns, but in silence. I was captivated. As someone who grew up in church, this was shocking. Church services were full of noise—prayers, songs, preaching. Even the so-called “moments of silence” left my mind racing: Am I doing this right? What’s the point?

But here was a different way—centering prayer, contemplative prayer, simply sitting in God’s presence with no agenda but to be. As I began practicing, the same Spirit who had met me years earlier seemed to come alive again. I felt His presence. I knew I was accepted. I was loved without qualification.

Building a Community Inside

For years I practiced alone, though I longed for a fellowship of men on the same path. I began writing to Prison Contemplative Fellowship and to Chaplain Ray, asking how we could start a practice group on my unit. Nothing happens quickly in prison. And when something good does begin, the Department of Corrections usually finds a way to bury it in bureaucracy—background checks, endless forms, delay after delay.

At last, a local pastor named Richard Wing reached out. He had spoken with Chaplain Ray and was recruiting volunteers. A group was finally going to begin. But then, in typical fashion, the senior chaplain told me the program would run on another unit instead of ours. “Thank you for the idea,” he said. “You get the credit.”

I didn’t want credit. I wanted brothers.

Thankfully, a few weeks later, he returned to say they’d reconsidered—the group would be held on my unit after all. And then, COVID hit. Everything stopped. To make matters worse, I was moved to another unit.

But by God’s grace, when things reopened, the decision was made to start the program at the unit where I was. We began with four or five men. At its peak, seventeen. By the time I left, it was back to a handful—but still alive. That same group still exists today, but I can’t be physically with them. When you walk out the gate, you walk out alone.

The Loneliness of Release

Compared to many, I was fortunate when I was released. At sixty-nine, I inherited a home in a retirement community. I had retirement income to live on, a car, and the stability most returning citizens can only dream of.

But I didn’t have community.

For the last years of my sentence, my true fellowship had been my contemplative prayer brothers. We shared silence together, and in that silence we found God. They were still inside. I was outside. I will always be with them in spirit, but I also longed for contemplative community.

I searched for contemplative prayer groups in my area, but living in a retirement town meant many of them shut down during the summer when snowbirds migrated north. I found myself back to practicing alone.

An Unexpected Gift

And then, after nearly a year—Providence. I discovered an online contemplative group that met on Sunday nights, made up of formerly incarcerated people and a few who had ministered inside. Because of my parole restrictions, I couldn’t use much technology myself, but a roommate off supervision let me join through his setup.

At first, I didn’t know what to expect. But as I listened, I was humbled. In my prison group, I had been the one with the most experience. In this Zoom circle, I encountered men who had been practicing for decades. Some of those present had been blessed to have known Father Thomas Keating personally and carried his wisdom into our circle.

I didn’t know such people existed. I was overwhelmed—and deeply connected.

Even separated by miles, we were not truly separate. What united us was not proximity or circumstance, but the Spirit of God. Sitting together in silence, we became one body. That kind of fellowship is foreign to the world, but it is real.

The Invitation

So I return to the paradox. Leaving prison was indeed the happiest and the saddest day of my life. I left behind brothers, but I also stepped into a wider fellowship I could never have imagined.